On célèbre cet automne le centenaire du surréalisme. Le mouvement fondé par André Breton est ainsi fêté au Centre Pompidou et en divers autres lieux de la capitale. Le Musée du Luxembourg (Paris) expose quant à lui du 9 octobre 2024 au 2 février 2025 les œuvres de la Brésilienne Tarsila do Amaral (1886-1973) [commissaire : Cécilia Braschi].

Elle fut une artiste importante de la modernité brésilienne quoique moins scrutée que des figures comme Lygia Clark ou Helio Oiticica. Ces derniers sont certes plus jeunes, et Amaral a connu quant à elle une autre époque. Celle du premier modernisme à laquelle les surréalistes ont grandement participé.

En somme, elle devance de quelques années une Frida Kahlo, qui avait eu des mots peu amènes pour la « bande à Breton », qu’elle voyait comme un « vieux cafard », quan elle vint à Paris à la fin des années 1930.

La vie d’Amaral oscille entre deux pôles, Paris et le Brésil, où elle nait. De Paris, où elle gravite dès 1920, elle retire une solide formation artistique. Du Brésil, elle tire un imaginaire pétri de « primitivisme indigéniste ».

Et toujours elle garde à distance un œil sur la culture de son pays, serait-ce par l’entremise de l’écrivain Oswald de Andrade, qui devient son compagnon. Blaise Cendrars est l’exact contemporain d’Amaral. Il voyage au Brésil dès 1924, de surcroit avec un bras en moins, perdu lors de la guerre de 1914-18. Tout ça pour dire que durant cette époque charnière de l’entre-deux guerres, certains s’ouvrent au monde quand d’autres se cantonnent à une position ethnocentrée. Quelques artistes ou écrivains ont en effet entrevu comme par préscience le devenir mondialiste des sociétés humaines. D’ailleurs, Cendrars rencontre Amaral en 1923 et lui présente le monde artistique parisien : Brancusi, Picasso, Braque, Léger, Delaunay… Les grands esprits se rencontrent.

Andrade publie en 1928 le manifeste anthropophage, grandement inspiré d’une œuvre d’Amaral, Abaporu. Ce texte constitue un jalon important dans l’évolution de la culture brésilienne, on en trouve des traces jusqu’à nos jours dans les œuvres d’une artiste comme Adriana Varejao.

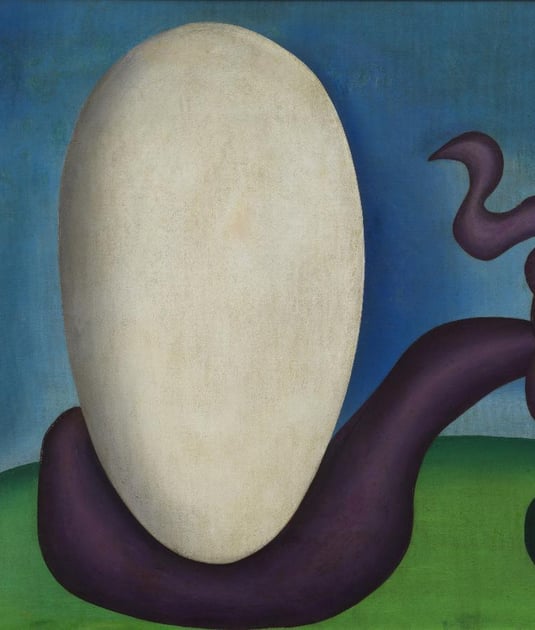

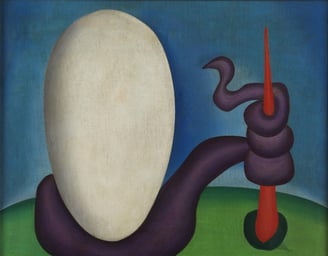

Au début des années 1920, Amaral, étudiant à l’académie Julian (Paris), peint des portraits de femmes relativement symbolistes et années folles. Elle sera toutefois plus connue pour ses compositions tropicales étranges. Dans A Cuca(1924), des animaux s’ébrouent dans une végétation stylisée. Dans Urutu (1928), un serpent s’enroule autour d’un œuf et agrippe un mat pointu. C’est politique et sexuel à la fois, pas très loin de certaines œuvres qu’Alberto Giacometti imagine au même moment.

Dans Terra (1943), un corps minéral allongé dans la pierraille du désert semble évoquer les luttes paysannes même si l’artiste, maintenant une distance salvatrice avec le réalisme social, privilégie les représentations oniriques.

En tout état de cause, de nombreux peintres réalistes actuels, qui lorgnent du côté d’un art naïf à la Douanier Rousseau, seraient bien inspirés de regarder aussi l’œuvre d’Amaral. Ces artistes s’apercevraient qu’en son temps, la Brésilienne avait déjà défriché pas mal de terrain. Tarsila do Amaral est sans conteste un des chainons manquants de l’art.

L’exposition sera ensuite présentée au Musée Guggenheim Bilbao (février - juin 2025).

Tarsila DO AMARAL Auto-retrato (Manteau rouge) [Autoportrait (Manteau rouge)]. 1923. Huile sur toile. 73 x 60,5 cm. Museu Nacional de Belas Artes, Rio de Janeiro

Tarsila DO AMARAL Urutu (Détail). 1928. Huile sur toile. 60,5 x 72,5 cm. Museu de Arte Moderna, collection Gilberto Chateaubriand, Rio de Janeiro

Tarsila DO AMARAL

Le chainon manquant

Clémentine Vermont

This fall marks the centenary of surrealism. The movement founded by André Breton is being celebrated at the Centre Pompidou and in various other locations across Paris. From October 9, 2024, to February 2, 2025, the Musée du Luxembourg (Paris) will exhibit works by the Brazilian artist Tarsila do Amaral (1886-1973) [curated by Cécilia Braschi]. Amaral was an important figure of Brazilian modernism, although she has been less scrutinized than figures like Lygia Clark or Helio Oiticica. These latter artists are certainly younger, while Amaral belonged to an earlier period—one shaped by the first wave of modernism, to which the surrealists greatly contributed. In essence, she predates Frida Kahlo by a few years, who had little kind to say about Breton’s “group,” referring to him as an “old cockroach” when she came to Paris in the late 1930s.

Amaral’s life oscillated between two poles: Paris and Brazil, where she was born. From Paris, where she moved in 1920, she gained a solid artistic education. From Brazil, she drew an imagination steeped in "indigenous primitivism." She always maintained a critical distance, keeping an eye on her country's culture, sometimes through the lens of the writer Oswald de Andrade, who became her partner. Blaise Cendrars, Amaral’s exact contemporary, traveled to Brazil as early as 1924, despite having lost an arm during the First World War. This serves to illustrate how, during this pivotal period between the two world wars, some people were opening up to the world while others remained ethnocentric. A few artists and writers seemed to have intuitively anticipated the future globalized nature of human societies. Cendrars met Amaral in 1923 and introduced her to the Parisian art scene, including figures such as Brancusi, Picasso, Braque, Léger, and Delaunay—great minds meeting.

In 1928, Andrade published the Manifesto Antropófago (Cannibalist Manifesto), greatly inspired by one of Amaral’s works, Abaporu. This text became a major milestone in the evolution of Brazilian culture, with its influence visible today in the works of artists like Adriana Varejão.

In the early 1920s, while studying at the Académie Julian (Paris), Amaral painted relatively symbolist portraits of women from the Années folles. However, she became more renowned for her strange tropical compositions. In A Cuca (1924), animals frolic in stylized vegetation. In Urutu (1928), a snake coils around an egg and grips a sharp mast. The work is both political and sexual, not far removed from certain pieces Alberto Giacometti was creating at the same time. In Terra (1943), a mineral-like body stretches across the desert rubble, seemingly evoking peasant struggles, though the artist maintained a saving distance from social realism by favoring dreamlike representations.

In any case, many contemporary realist painters, who lean towards naïve art in the vein of Douanier Rousseau, would do well to study Amaral’s work. They might realize that the Brazilian artist had already broken much new ground in her time. Tarsila do Amaral is undoubtedly one of the missing links in the history of art.

The exhibition will next be shown at the Guggenheim Museum in Bilbao (February - June 2025).